|

Grayson Perry "ISMS"

Paul Scott: "The

Accuracy of Artillery, Radar Produce of Israel"

Lenny Goldenberg:

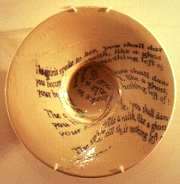

"Glaze Book"

Karen Densham"

Spider 1998"

Janet Williams"Babel

Books 1998", (Fired books)

|

Words

are increasingly making their mark on contemporary

studio ceramics. Along with printed surfaces and

figurative forms and decoration, words are part of a

postmodern drive to give ceramics more meaning and

accessibility. These aims should be particularly

facilitated by applying words to ceramic surfaces. The

universalising modernist argument however, would point

to indigenous language differences curtailing these very

intentions and restricting potential audiences just as

the self-referential language of most studio ceramics

excludes the uninitiated. Ceramics bearing words, though

apparently reverting to a comparative vernacular, at

least say something new, unlike the lingua franca

of much mainstream studio pottery which declaims empty

platitudes or endlessly repeats stale cliches.

Insistence

on function, harmony of form and decoration, the

expressive touch rather than the expression of thought,

have long suppressed words as extraneous to the studio

potter's creative language. (1) The

common currency of communication, words are seemingly at

odds with the refined aesthetics, specialised technical

skills and forging of personal visual vocabularies

expected of the serious ceramist. Words belong on

mass-produced souvenir and commemorative ware, on dog

bowls and jokey mugs, and these associations make

traditionalists view their incursion into studio

ceramics as deeply subversive and antithetical to the

dumb eloquence of its most revered creations.

The

exhibitors in Glazed Expressions - more concerned

with relevance than reverence - use words in defiance of

the orientalist, rural or cool design values which have

characterised studio ceramics but precluded engagement

with the everyday imagery and issues of Western urban

society. Today's ceramists might be seen as responding,

somewhat belatedly, to the phenomenal prominence of

words seen in fine art over the last four decades.

Sixties pop art first gave unprecedented visibility to

words in reflecting popular printed material and

mass-produced commodities. Later in the decade,

Conceptual art began to marginalise images and objects

to divert attention to ideas presented increasingly as

documentation and text. Theory, semantics, and the

critique of art itself flourished - as art. From the

1970s, feminist and political art added polemical texts

and provocative word/image alliances, and in the l980s

and 90s post modernist strategies of appropriation,

parody and ironic juxtaposition have added to the

word-count.

Inevitably

these currents, and the cultural and political climate

which shaped them, have impacted on ceramics. The use of

words in ceramics has gained momentum in Britain over

the last decade, developed by specialist potters and

artists from other disciplines wanting to express ideas

whose meaning depends entirely on this precise

combination. (2) Not all 'craft'

mediums have a technical and traditional basis which

allows words to be given an importance parallel to that

demonstrated by fine art. Clay though is uniquely

flexible, and is able to both respond to tendencies in

fine art and develop a conceptual language based on Its

own inherent properties and on the history and

traditions of ceramics, high and low - the mass-produced

and individual, the functional and decorative.

Over the

centuries words have been inscribed or printed on

ceramics as documentary and narrative texts; in

religious exhortations and quotations; in burlesque and

ribald verse; in moral and political messages. In some

cases slippery semantics were celebrated - puns were

inscribed on 19th century plates and tobacco jars -

underscoring the infinite malleability of both clay and

words. The two also enjoy a very ancient partnership

which firmly associates ceramics with vehicles for

conveying meaning as much as with vessels for containing

matter. It has been noted that: 'What the book is to

history, the pot is to prehistory... through the first

clay tablets of four and a half thousand years ago, the

pot and the book (share) a common geological

ancestry...' (3)

Ancient

Babylonians and Assyrians inscribed and impressed

writing into tablets of soft clay, oven-baked or

sun-dried. These flat tablets, inscribed on both sides,

numbered and laid out in sequence on shelves, anticipate

the familiar book form perhaps more closely than the

handwritten papyrus scrolls commonly identified as its

precursor. It is therefore probably not purely

coincidental that the book - the archetypal container

for words - is one of the most common objects replicated

or referenced in ceramics.

An early

example by Robert Arneson, Earth Book 1 (1973)

makes the geological connection but is also inscribed

with the title Secret Ceramic Glazes satirising

the technical obsessions and recipe retention associated

with potters - the glazes remain secret as the 'book'

cannot be opened. Another American, Richard Shaw,

includes books in many of his hyperrealist photo-silkscreened

porcelain object groups. Here they can be interpreted as

emblems of the 'literal', which itself can be defined as

close to the written word, as suggesting absolute

accuracy (which is appropriate to the detailed

simulations of Shaw's work) and as implying veracity

(which given the deceptive nature of his pieces, is

highly ironic).

The

closed books of Arneson and Shaw conceal content whereas

Lenny Goldenberg uses the device of the open book to

reveal its extraordinary reductive capacity as a vessel

for information distilled into words. Goldenberg's

recent series of press-moulded books often continues

impressed text and captions with three-dimensional

representations of the content projecting from the

surface. In Throwing on the Wheel Handbook the

text describing the steps in the process is

'illustrated' by sculptural hands which progressively

extrude the clay pot from the clay page - recalling

their ancient affinities The basic form of Goldenberg's

books also recalls mass-produced examples such as china

bible ornaments 'open' at the Lord's Prayer.

The

conjunction of allusions to the archaic and the

mass-produced also appears In works which relate

technically and thematically to the newspaper industry,

which daily generates billions of words. A number of

ceramists (including Goldenberg) have adapted the

industry's technology to impress words or whole texts -

where the ephemeral, expendable nature of newsprint

words act as reminders to the more enduring ones

impressed on ancient clay tablets. The primal link

between clay and words continues to develop in ways

which relate to late 20th century experience. A recent,

highly successful, teaching method for dyslexics

involves modelling clay words along with clay images of

the words' meanings based on dictionary definitions.

This enables dyslexics to make sense of the abstract

symbols of the alphabet, and reverses the role of the

ancient clay tablets which were impressed not with the

sub-imagery of hieroglyphs or pictographs but the

abstract code of cuneiform - the earliest written words.

(4)

This

palaeographic reference was explored in the late 60s in

vessel forms with Impressed newspaper texts by American

John H Stephenson, who described them as 'the result

more of a fascination with the concept of 'contemporary

cuneiform' than a gimmick... a recycling of writing in

clay markedly different from the original form.'(5) More recently, Paul Mason's

combinations of impressed newspaper texts with

palaeontological forms have evoked similar connections

between the ephemeral and enduring. Mason has juxtaposed

sports columns, where information is both compellingly

current and rapidly redundant, with constructed fossils

-extinct life-forms which have nevertheless survived for

millennia. The immediate yet disposable appears in

paradoxical relationship with the dead but apparently

indestructible(6).

Other

levels of paradox are involved in the frequent

replication of newspaper text in contemporary ceramics.

In fine art, Picasso's papiers collées of

1912-13 gave (actual) newspaper a central role,

exploiting its potential for paradox and wit in

questioning painting's traditional illusionistic role.

Ceramists like Richard Shaw (whose fondness for

reproducing books is matched by an enthusiasm for

newspaper) use it both to accentuate and undermine

illusionism. Shaw's Canton Lighthouse (1985) (7)includes a ginger jar, paint pot and

book, whose printed surfaces and labels accord with the

objects: but in the newsprint covered 'house', surface

and structure punningly part company. His Journals with

Paper Ship (1993) presents ceramic newspapers as

themselves, as a weighty pile, supporting an equally

heavy 'paper' ship.

Shaw's

work relates to the Photo/Hyperrealist continuation of

Pop Art but ultimately many of its devices recall 17th

century trompe-l'oeil still life painting where

manuscript sheets and musical scores (such as those now

updated by Maria Geszler) appeared as a particular

demonstration of illusionistic skill. The comparable,

though inverted, visual paradox involved in ceramic

sculpture of this type is intensified by the dense

detail of newsprint words.

Apart

from its general role in making a visual impact on the

viewer, newspaper sources also provide specific written

content which can lend authority to a ceramic statement.

This is the case with Paul Scott's Free at Last

(1990) (8) which repeats the

newspaper photograph of Mandela's freedom salute,

alluding to his transformation from potent symbol of

black resistance to media icon, commodified and emptied

of real meaning. One side of the piece includes a

paragraph from a Guardian article drawing

attention to the reality of events in South Africa

between Mandela's imprisonment and release. Collaged

over the images, the words restore them to their proper

place within a complex and uncomfortable political

reality.

Freehand

words have a different resonance to typographical forms

and are not unfamiliar as an attractive decoration in

studio ceramics.(9) Others have a

style and meaning which borrows from contemporary

subculture - the territorial markings of graffiti gangs,

daubed subway slogans and toilet-wall scrawlings - the

unofficial writings of public places. Hugo Kaagman, a

former graffiti artist, has used spray-painting with

stencils as 'modern pictographs', and has developed

'punk ceramics' and other subversive clay idioms He uses

words whose forms and meanings suit his irreverent

commentary on ceramics tradition (Delft and Chinese in

particular), art history, popular imagery etc. Grayson

Perry's similar repertoire of iconoclastic fragments of

high and low culture, introduces a personal note in

images and words relating to his transvestite identity.

His classically-based pots are subverted by deliberately

meretricious decoration accentuated by crudely scratched

confrontational words.

More

overtly-politicised confrontation is increasingly

encountered on plates. The word/image combination which

decorates commemorative plates is now used to redirect

attention to the plate's functional role in works

presenting a critique of consumer society at its most

literal. Both Paul Scott and Conrad Atkinson have used

allusive imagery and judicious continuations of scripted

and printed words as reminders of Third World famine,

Western self-indulgence and the implication of the

consumer in the conditions and actions of countries

which export the produce we eat. Serving up such

unappetising truths on a plate, brings them home in the

most direct manner.

The

dinner-plate is now an arena for life or death drama

where carnivores may dice with the by-products of

government negligence and agriculture's impoverished

ethics. 'BSE, 'CJD' and 'E. Coli' could be inscribed on

many a plate but Karen Densham merely impresses the word

'MAD' in wobbly letters under the image of an equally

unsteady bovine. Densham's Mad Cow (1995) belongs

to a series based on the traditional Staffordshire cow

creamer, and with the word 'mad' the traditional image

is confronted with a topical reality. Three other pieces

bear the words 'fat', 'silly' and 'old' which prefix

familiar insults. juxtaposed with allusions to one of

the best-loved and most cozily collectible items of

pottery, these epithets highlight the disparity between

sentimentalised idea and misogynistic idiom. Densham can

say a great deal using a single word conjoined with the

representation and actuality of essentially functional

ceramic form.

In

considering the potential of word/ceramic continuations

to challenge complacent convention and Influence ideas

we need only think back to 1917, when Duchamp exhibited

his Fountain - a mass-produced porcelain urinal. This

demonstrated the Iconoclastic potency of combining a

functional ceramic with just one word (and an Initial) -

'K. Mutt'. By replacing the printed name of the

manufacturer with this signature, Duchamp identified the

urinal as an art work. Devoid of any aesthetic quality

and emblazoned with a word which seemed to compound

Duchamp's insolence, ('mutt' was colloquial English for

'fool') Fountain presented the idea as the focus of

interest. Fountain remains one of the most revolutionary

and Influential works in the canon of modern art. More

than any of Duchamp's other 'ready-mades' it anticipated

both the Pop and Conceptual movements and the subsequent

relentless expansion of words into visual art, as ideas

displaced aesthetics. For much of the 20th century,

the word has been censored in studio ceramics, but

contemporary practitioners are now claiming back ancient

territory and adapting it to the creative Imperatives of

today. Though some may share Duchamp's iconoclasm, their

motivations are exceptionally varied in re-examining the

relationship between the matter of clay and the meaning

of words.

@ Dr

Stephanie Brown 1998.

1)

As late as 1991 a survey of contemporary international

crafts which illustrated an eclectic range of innovatory

studio ceramics included only one example of decoration

with words (Yo by Adrian Saxe, USA). See Martina

Margetts (Ed.), International Crafts, London, 1991, pp

18-51.

2) In America, where craft

and fine art practices have been more integrated, words

have been far more common in ceramics from the Pop era

on. Robert Engle, Les Lawrence and Jim Melchert are

amongst those making notable works, but Robert Arneson

consistently explored word/clay meanings in sculptural

ceramics from the early 60s to the early 90s. Arneson

pioneered many of the approaches which now preoccupy

contemporary ceramists, including using imprinted and

graffitied words in visual and verbal puns,

investigations of ambiguity and paradox in materials and

artistic activity itself, commentary on 'tasteful' and

industrial ceramics, scatological statements,

politically campaigning and subversive texts.

3 Ivor Robinson, 'The

Book: comparative forms and creative acts', Les Bicknell

(Ed.), The Book as Art, Essex University, 1994, up.

4 The Davis Dyslexia

Programme, devised in the USA in 1982, has a 97% success

rate. See 'Rewriting the alphabet in clay', The

Independent (Education supplement), 16 July 1998, pp

4-5.

5 Lee Nordness, Objects

USA, New York, 1970, u.p.

6 and 7. See Paul Scott,

Ceramics and Print, A&C Black 1994. pages 34, 99.

8 See Hot off the Press

,Paul Scott, Terry Bennett. Bellew 1996 page 30

9 Words in this case are

used for decoration or simulation without regard for

meaning, and may range from adaptations of the

calligraphic arabesques on Hispano-moresque pottery, to

pastiches of 17th century slipware. |